Written by: Ethan Moore (@Moore_Stats)

Follow us on Twitter! @Prospects365

It is tempting to think that we are currently tracking everything we possibly can in a baseball game, but this is untrue. Although we have a sea of data relating to the position of the baseball at all times, there are still plenty of aspects of the game that are completely ignored in our data collection (as far as I know). The foremost aspect that is ripe for analysis once we begin tracking it, in my opinion, is data relating to whether each swing was early, on time, or late which I will refer to as swing timing data.

Although we have understood for decades that the timing of a swing can influence whether the pitch is hit or not, there is no publicly available data about this piece of information! Throughout the data revolution in baseball, the timing of each swing has simply not been recorded. One likely reason for this is that it is difficult to figure out whether a swing was too early, too late, or on time, but that didn’t stop me from trying!

Armed with a bit of sample data and some imagination, I set out to unearth a whole new area of baseball analysis that may be an important part of the impending arms race of MLB teams competing to find the best new uses for their Hawkeye data.

Sample Data

For this project, I watched all 160 total whiffs from 5 different hitters in 2020 and did my best to label each swing as being Early, On Time, Late, or a Checked Swing. This data was collected to give us an idea of what kinds of questions we could answer with comprehensive swing timing data and NOT to actually answer any of those questions with certainty.

I selected five sample players who had different offensive profiles and watched each of their 2020 whiffs (as of August 13th), grouping them by their timing, early, on time, late, or checked. These hitters were:

DJ LeMahieu: High Production, Low Whiff (88th percentile xwOBA, 99th percentile Whiff Rate)

Eddie Rosario: Low Production, Low Whiff (22nd, 87th)

Fernando Tatis, Jr.: High Production, Low Whiff (87th, 21st)

Mike Zunino: Low Production, High Whiff (0th, 6th)

Max Muncy: Average Production, Average Whiff (52nd, 52nd)

By choosing a diverse group of hitters, I was able to expand the types of questions I could ask from this kind of analysis! Without further adieu, here are the most interesting questions that I think could be answered with comprehensive swing timing data.

#1. Why Do Hitters Swing And Miss?

Hitting a baseball is hard. But why? In my view, hitting has 3 main components: timing, power, and barrel placement. You need all 3 to make hard contact. If your swing only has two of the main components, you can expect to whiff or get weak contact.

As you can see, I believe not all whiffs are created equally and that there are two main types of whiffs which I will name and describe here.

A Type 1 Whiff is a swing with power and good timing, but the bat is in the wrong place. The whiff is a result of the hitter’s miscalculation of where the pitch will be in the strike zone when it crosses the plate. Against Jakob Junis on August 7th, Rosario swung under a high Fastball. His swing was both powerful and on time, but was too far under the ball, resulting in a Type 1 Whiff.

In contrast, a Type 2 Whiff is a swing with power and good barrel placement but poor timing. This type of whiff is the result of the hitter’s miscalculation of when the pitch will cross the strike zone. These occur when the hitter swings too late or too early. On July 24th against Hyun-Jin Ryu, Mike Zunino was too early on a Changeup.

This frame shows that Zunino had good barrel placement. The path of his bat intersected the path of the ball (because the two are overlapping), but…

the next frame shows that Zunino swung too early, so his bat missed the ball.

In conclusion, my theory is that there are two types of whiffs. Type 1 Whiffs occur when the pitch moves differently than the hitter expects it to. Type 2 Whiffs occur when the pitch is slower or faster than the hitter expects. A third type of whiff would be a whiff that follows the definition of both previous types, and these are typically pretty damn ugly.

Having comprehensive swing timing data could essentially prove or disprove this theory and help us better understand why hitters whiff.

#2. Do Different Hitters Have Different Whiff Profiles?

With current public data we can quantify which pitch types give each hitter the most trouble at the plate, but looking at timing can give us another layer of understanding as to why a hitter struggles with certain pitches.

Between 2009 and 2010, Jose Bautista transformed himself from a fourth outfielder into the league leader in Home Runs. In this ESPN feature (which I highly recommend), Bautista mentions that he added a leg kick between 2009 and 2010 which helped improve his timing at the plate.

Essentially, Bautista attributed one of the biggest player development success stories of the decade to fixing his swing timing, something we do not currently measure. How many other players are currently struggling as a result of fixable timing issues that are going unrecognized?

My theory is that every hitter has certain tendencies with his timing. Here is an example of the kind of quantification of timing profiles this data should be able to provide for us to help diagnose and understand our hitters:

On this plot, the height of the bars represents total whiffs on Fastballs. Tatis has the most, LeMahieu has the least. That is important info. On Fastball whiffs, Muncy is the best at being on time and Rosario is usually late. Also potentially important!

What about whiff profiles for Curveballs, for example?

We can see that Tatis has whiffed the most from Curveballs (although a larger scale analysis should probably be looking at whiff rates, not raw whiffs). When Rosario has whiffed on Curveballs, he has always been early. When Zunino has whiffed on Curveballs, he has always been on time. Interesting!

Looking at the bigger picture, we can easily see that our hitters have whiffed more on Fastballs than Curveballs this season, that hitters are typically late on Fastballs when they whiff and early on Curveballs when they whiff but that this is not always the case. Similar charts and trends could be analyzed for all pitch types and in many different scenarios.

We could also answer questions about league-wide trends like whether players who have good timing on their whiffs tend to be more productive when they aren’t whiffing:

To answer the question: Yes, there is a positive association in the sample data! (No, this trend should not be extrapolated to the league at large at this time!)

In my mind, there could be lots of predictive power in a swing timing variable that could help us better predict how a hitter is likely to do going forward. But whether this is the case or not, being able to visualize a hitter’s timing profile has a chance to be a valuable player evaluation tool going forward.

#3. How Do Other Factors Influence Swing Timing?

There are so many variables to what happens in a plate appearance, so which of those variables impact swing timing? Previous pitch? Pitch number of the plate appearance?

I’ve heard some anecdotal speculation that a hitter is more likely to have good timing on a pitch if they see it two times in a row. Swing timing analysis could test that! But more broadly, we would be able to better understand the interplay between subsequent pitches. Are batters more likely to be late on a high fastball when the previous pitch was a slow curve? Which pitch should the pitcher throw next after a hitter is late on a fastball?

Currently, we could speculate all day about the answers to these questions and try to estimate how pitches interact. With comprehensive swing timing data, we could essentially know for sure.

In my sample data, I was able to make a few fun graphs:

I found that our sample hitters were most commonly late on fastballs that came one pitch after another fastball, but were on time a fair bit of the time as well. Keep in mind, each observation you see above was a whiff. Offspeed pitches after fastballs in this data most commonly elicited a late swing. This all lines up with our existing understanding, which is a good sign!

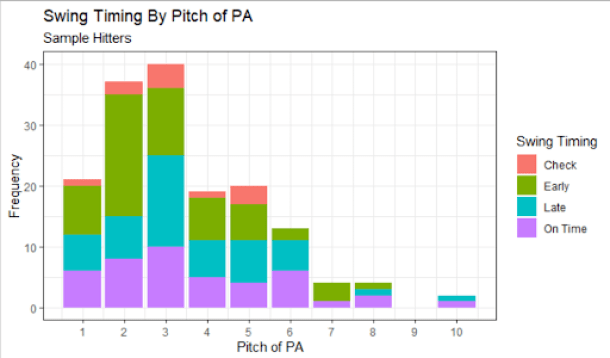

Additionally, we could look at whether hitters are more likely to be on time the more pitches they see in a plate appearance:

By tracking the heights of the purple bars, we can see that hitters in this sample were not more likely to be on time as the plate appearance went on. But is this the case for the rest of the league? We don’t know, but we would with swing timing data!

Conclusion

Hopefully this article has sparked your imagination and convinced you that there is plenty to learn about the game of baseball (especially the batter-pitcher interaction) from swing timing data. This article only focused on swings and misses from 5 MLB hitters in about 3 weeks of MLB play. Imagine how much we could learn from swing timing data on all swings by all hitters in all games!

Swing timing data is not currently available publicly (as far as I know), but it could be available in the not-so-distant future if Hawkeye is able to function as advertised. If it is, teams will have a great opportunity to use that data better than their competitors to gain a competitive advantage and as with any large new data source, it can be hard to even know where to start your analysis. But after reading this, I hope teams will begin by examining this topic as the potentially game-changing topic that it is.

Thank you for reading! If you have any comments or questions, please tweet me or DM me on Twitter @Moore_Stats.

Follow us on Twitter! @Prospects365